#30. A lot of good things don't get made because of too much thinking.

Disclaimer: as it says on the tin, I will not be selling you anything. But I'm going to mention my writing. But you couldn't even buy it if it was for sale, because it's not! Joke's on you!

So, after a very very long time, I finally buckled down and wrote a book about schizophrenia. For those of you who are new to me, I've got the schizophrenias--I started having symptoms fifteen years ago, and was officially diagnosed eight years ago. And it has been a helluva ride, and I've often thought about writing a memoir. But I didn't! I wrote a YA contemporary romance.

And folks, I love this book so much. It's about a teenager who has been developing symptoms over the last year and a half, and then they all come to a head, and bad things happen. But the bad things happening is not why I want to write it: this book does not have a sad ending. It doesn't have a neatly-tied-up ending, where everything is perfect, but it does have a hefty dose of optimism.

The Deep, by Jackson Pollock

I've always been a fan of modern art--my very favorite painting is The Deep, by Jackson Pollock, but my very favorite artist is Mark Rothko. Abstract art affects me in a way that other art doesn't, and I think it's because I have to bring my own meaning to it. The painting can't tell you what it's about: you have to come to terms with the painting and decide what it means for you.

Untitled, by Mark Rothko

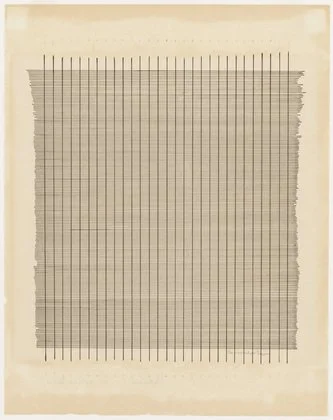

Anyway, several years ago I became acquainted with the works of Agnes Martin. I really love her art, which is extremely minimalist, yet organic. But I like her because she, like me, had schizophrenia. And she, like me, lived near the town of Cuba, New Mexico. We were even there at the same time, though I'd never heard of her (she passed away in 1999, and, despite having shows in the MoMA, she lived for 50 years in a little adobe home in New Mexico and had little contact with the outside world.)

Like me, she liked Rothko, and said of his art that he "reached zero so that nothing could stand in the way of truth." And that's the way that she painted--very minimalist grids and lines, in pale and dirty colors.

Tremelo, by Agnes Martin

Here's the deal: I can't explain to you why I like Agnes Martin, other than to say that we have several things in common, and that I find her paintings moving. For this Christmas I got myself (my wife and I buy our own presents and then "give them" to each other) a print of Martin's, and when I showed it to Erin, she just said "okay." She was not terribly impressed.

Agnes Martin said something, though, that I find fascinating and relatable: “A lot of good things don't get made because of too much thinking.”

Going back to my YA novel, I've been thinking about writing a schizophrenia book for the better part of a decade, and I've even tried before: I wrote a 130k word monstrosity about a schizophrenic character who was surviving the apocalypse. I also wrote a couple chapters of my memoir. But none of it was ever any good.

And then this book just came to me: I had an outline in three hours--an outline that I knew was good--and then I had a draft in two months--a draft that I hoped was good. It's not the normal way that I write books. I have long been an outliner--a thinker--but this thing came from my heart, not my head.

To be fair, the book is extremely autobiographical, minus the age difference, so I HAVE been thinking about this stuff for a very long time. I just had never written it down in a story.

Will it be good? Too soon to say. I love it. I've had positive feedback from alpha and beta readers. My agent is currently reading it. But I think that books are like abstract art: there's no "perfect" book that you like because all the right things line up in the right places. Books are something that you interact with, and interpret, and insert yourself into. You see yourself as much as you see the writer.

At least, that's my goal. Maybe, two years from now (publishing is slow) you'll get to read it and decide for yourself.

Bits and Bobs from the News

#1. The First Thanksgiving

HEY. If you live in the United States, this week is Thanksgiving, which is my favorite of all the holidays. But some of what you've been taught about the original Thanksgiving is not entirely accurate, in the sense that it's hardly accurate at all.

For starters, the reason for the feast is unknown, but historians don't really believe that the Plymouth Colony "invited" the Wampanoag. Some accounts indicate that the Pilgrims were just having a feast--which was, truly, a feast of harvest thanksgiving--and the Wampanoag just happened to be walking by and stopped in to share food. The other notable account is that the Pilgrims were firing their guns in the air in celebration (because Americans are going to America), and the Wampanoag heard the shooting and hurried over because they thought a battle was going on. Either way, they go there. And the feast, it is generally believed, consisted of about 50 Pilgrims and 90 Wampanoag.

But what did they eat? Not turkey and not pies. There are good accounts that the Wampanoag brought five deer, to supplement the Pilgrims' fowl, and that this deer was probably cooked as a thanksgiving stew. They also would have had cornmeal, succotash, pumpkin, and cranberries. ALSO: probably eels, because it was easy to catch eels right there and Pilgrims ate a lot of eels.

As for where the Myth of Thanksgiving, people in America have been having unofficial thanksgiving feasts off and on for a long time. It wasn't until 1841 that the concept of "The First Thanksgiving" ever appears in print, and it wasn't until Abraham Lincoln when it was made a national holiday--he kinda hoped it would unify the country. (Spoiler: it didn't work.) It was the writer Sarah Josepha Hale, who had been petitioning the government for the holiday, who canonized the turkey, potatoes and pie menu that we all know today.

Anyway: Happy Thanksgiving!

#2. Kissing Is Super Old, Says Science

I write books with romance in them, and people kiss, and I never know how to describe kissing. But do you know who is even worse at describing kissing than I am? These scientists quoted in Scientific American: "non-agonistic interaction involving directed, intraspecific, oral-oral contact with some movement of the lips/mouthparts and no food transfer." Ooh baby, talk dirty to me.

Anyway, the reason they needed to define kissing was because they were trying to figure out just how old the practice of kissing is. And the way they do this is look for animals that ALSO kiss, and trace back to our nearest common ancestor. So, we homo sapiens are closest related to chimpanzees, and they kiss, so we conclude that whatever species existed when we branched off must have been a kissing species.

Well, they did the research, and they have declared that we humans and apes have been locking lips for the last SIXTEEN MILLION YEARS. And yes, they made a special note that Neanderthals kissed, and because we have a little bit of Neanderthal DNA (humans have about 2% Neanderthal DNA--bonus fact) then humans must have been kissing Neanderthals!

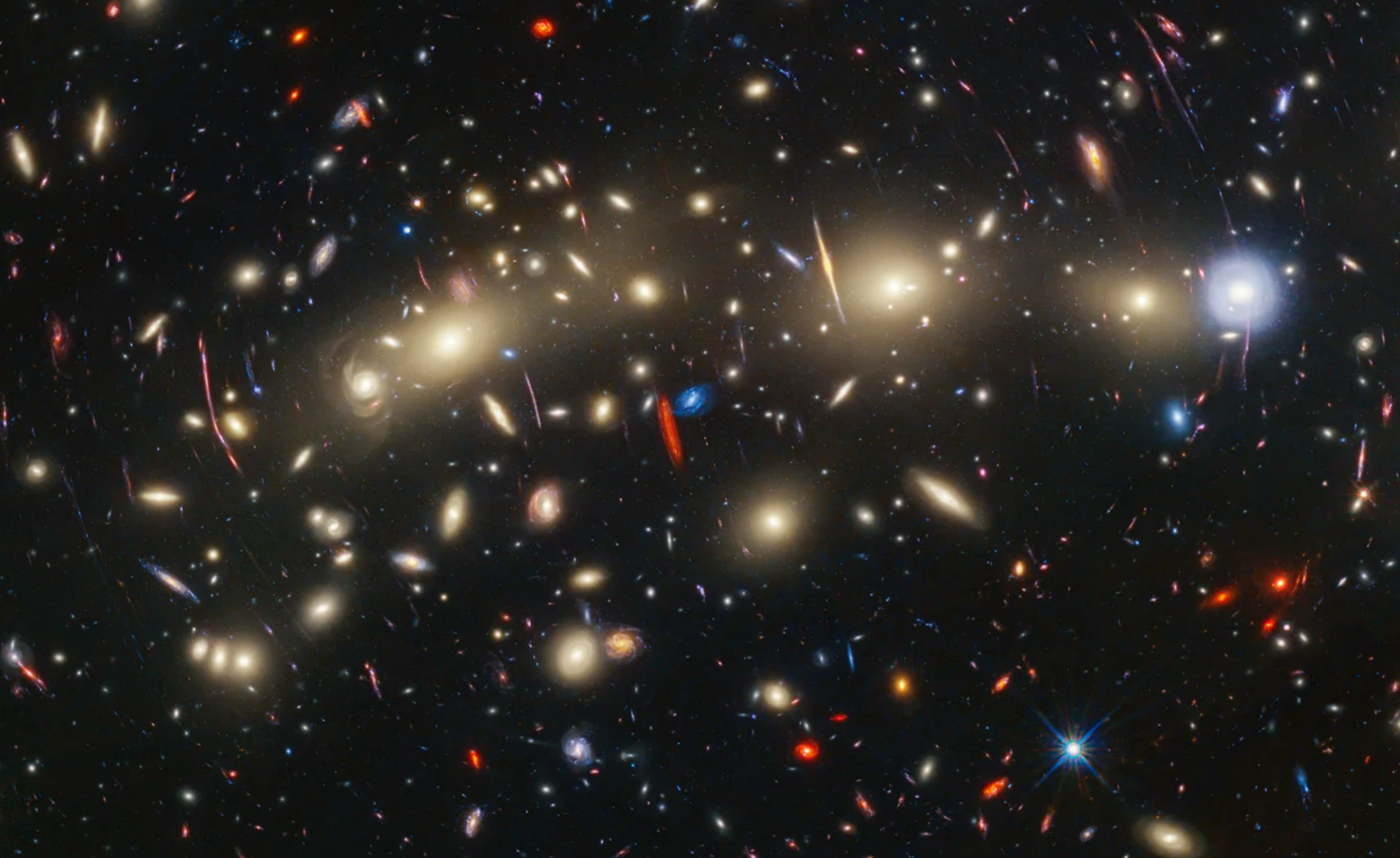

#3. Have We Found THE VERY FIRST STARS??

Now that we have the James Webb Telescope, which is an amazing feat of human invention, we're finding out all kinds of crazy things. And it has found these stars (pictured) that are super old and have the chemical makeup of what we would expect the earliest stars to have.

These are in the galaxy LAP1-B, and they're 13 billion years old--so old, that we can only see them because we're looking THROUGH a different galaxy and using its gravity as a kind of magnifying glass. (How did we know we could do this? I don't know--some scientists were super smart or something.) Anyway, seeing how the whole universe is less that 14 billion years old, these had to have popped up very early.

But the biggest indicator is that these stars are "pristine" in that they have almost no trace of any heavier elements (like, say, oxygen). These things are just the basics: hydrogen and helium and the like. Which makes sense if they have not been around very long, and have not had time to develop heavier elements. Anyway, I just think we should give astronomers a raise.

#4. How Do You Tell FUTURE CIVILIATIONS Where You Stored The Nuclear Waste?

So, you guys know that we have a lot of spare nuclear waste hanging around, and we put it in barrels, and then we encase them in concrete, and then we bury them (or something similar). The problem is this (and it's kind of existential): What if, in the future, we wipe ourselves off the map, either through war or disease or climate change or just a good, old-fashioned meteor? And then some plucky survivors live through the apocalypse (presumably this is during a YA novel) and they rebuild civilization, and THEIR archaeologists start to dig up the Statue of Liberty?

Well, the thing is, imagine this takes place 100,000 years from now. The Statue of Liberty, much as Hollywood would say otherwise, will not exist. Roads, buildings, most everything, will be gone. We'll probably have some large earthworks--like the pyramids, and the concrete foundations of major structures, and Mount Rushmore--but everything else will be gone. And Future Us wouldn't know where the Big Pile of Nuclear Waste is, but let's dig for artifacts in the deserts of Nevada!

So, experts have been trying to figure out what we could build to put on top of the nuclear waste that is a clear sign to people--who do not speak our language--to "Do Not Dig Here." (Because, womp womp, the halflife of uranium 235 is 700 million years.)

According to Scientific American: "In the 1980s and 1990s, task forces convened scientists, artists, science-fiction writers and semioticians to design warning systems that were intended to deter drill crews or archaeologists living thousands of years in the future. Their proposals were dramatic: vast fields of concrete thorns bristling from the desert floor; monolithic slabs etched with multilingual warnings (“this place is not a place of honor ... nothing valued is here”); and signage depicting the anguished face of Edvard Munch’s The Scream."

Anyway, the point is: we have a lot of problems we don't know how to solve, but here's an even bigger problem we also do not know how to solve.

Distractions and Diversions: Thanksgiving Style

Remember back in 1999 when no one used to brine their turkey, and then Alton Brown changed everything and now everyone brines their turkeys? Well, he is back with an all-new show, and he launched it this week with an update on The Proper Way To Cook a Turkey.

Have you, like me, totally screwed up cooking your turkey and it's still raw at dinnertime? Well, Binging with Babish takes on ALL the common Thanksgiving mishaps, screwing everything up (and then fixing it) so you'll be prepared in case of calamity.

And if you're looking for ALL the answers to ALL your Thanksgiving dinner problems, J-Kenji Lopez Alt is here to answer everything in this hour-long video that is PACKED with good information.

Happy Thanksgiving! Enjoy your eels!