#23. And may there be no sadness of farewell

When I was much younger—from 1997 to 1999—I was a missionary for the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints. I was young, very young. Men typically went at 19 years old, at the time, and so did I, and I was called to serve in the Four Corners area. Now, this was before the internet existed in any meaningful way—there was certainly no Wikipedia—so I knew virtually nothing about New Mexico before I got on the plane and flew there on April 9, 1997.

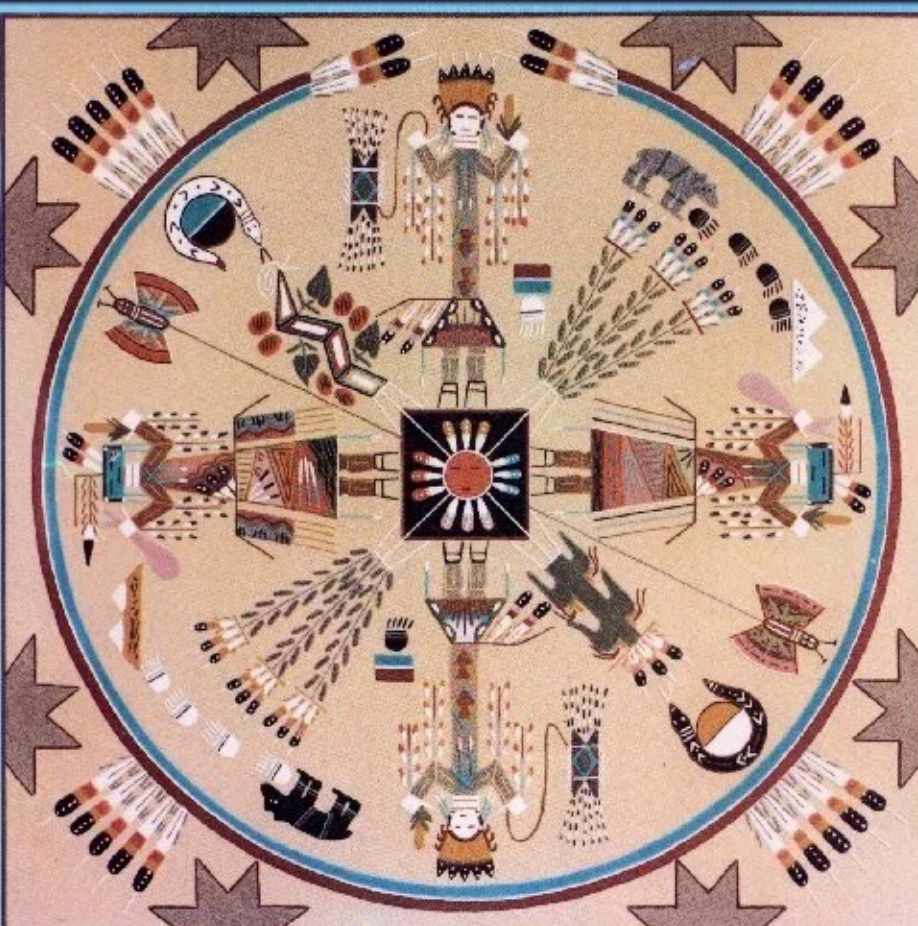

One thing I knew absolutely nothing about was Native American history. Sure, I’d been around it, at least a little bit, but again, not in any meaningful way. I’d seen some cliff dwellings down by Lake Powell, and I’d seen some powwow performers at the Utah State Fair, but I probably couldn’t have named more than one of the five tribes in Utah (yes, I did know the Utes)—and there was no way I knew about the 16 tribes that lived in the Four Corners region.

And still, I was sent to a very remote part of the Navajo Reservation—a little backwater spot called Pueblo Pintado—and was expected to teach the gospel. And I was completely, utterly unprepared for what I encoutered.

Now, let’s get one thing out of the way right now: I had some wrong ideas. I had biases. I have bigotry, both passive and active.

While we got training in how to teach the scriptures, we did not get training in what the culture was like. When I, little Mormon that I was (this was back when we still called ourselves Mormons) tried teaching the Diné people, I didn’t even know they were called the Diné. I’d never heard that word—the name the Navajo people call themselves. I was so completely out of my depth. I remember teaching the Word of Wisdom (the well-known LDS teachings about food and drink, and saying “you can’t drink tea” only to have the little grandma I was teaching ask “what about Navajo tea?” And I didn’t know what Navajo tea was. And when I told them “no drugs” they would respond “what about peyote?” And I had no idea, because no one had told me about these things.

But the one place where my bigotry was raging is that I felt completely confident that the Navajo were either liars or lazy, or both. Because they would tell us they would come to church, they would tell us they would be at an appointment, and then it would never happen. They committed to anything we asked—they just never followed through.

(On this note: I had one companion—and this is not how things are supposed to work, so don’t think we were all like this—whose first question on meeting a Navajo was “Have you ever thought about getting baptized?” Point blank, invite them to be baptized. And if they said no? Then he wouldn’t even bother teaching them. At the time I was leery of this practice, but I understood it: because if they would agree to everything—lessons, reading, church meetings—and then not come at all—then what was wrong with jumping straight to the punch?)

Anyway, this newsletter is not to badmouth my mission, but to tell you how I got thoroughly and completely changed.

EXPOSITION: HOW A MISSION WORKS

There was a man I met, months after serving on the reservation, named Richard McNeill. I had come to know the McNeill family very well, because they were extremely friendly to missionaries—they had five sons, two of whom were on their missions elsewhere while I was in their hometown of Milan, New Mexico. I grew intensely close with them—I was going through a lot of health problems, and Lisa McNeill, the family matriarch, helped me with therapies. I was also going through a lot of personal struggles, some of which involved companions.

(To be honest, I don’t know who these missionaries are, but this was on my mission and this is what I looked like. But more sunburned.)

Here’s a thing you have to understand about LDS missions: you have a companion, who is someone you do not choose but who is assigned to you, and you live with them for an indefinite amount of time. You’re with this person 24 hours a day, sleeping in the same room, doing every waking thing together. The only respite you get from an annoying companion is to go to the bathroom and stare at the mirror for a while, or to go on “splits.” Splits are when you and your companion meet up with two other priesthood holders, and each missionary goes with one of them, and you’ve doubled your workforce. Sometimes, these splits were done when two companionships would combine, but often they happened when members of the local congregation helped out.

(Mud is the perpetual enemy of missionaries on the reservation.)

I had two weird companion problems on my mission. (I had plenty more weird companions, too, but they probably thought I was weird myself.) In one instance, my companion transferred out of the area and I was supposed to get a brand new missionary (we called them “greenies”), but my greenie decided—at the airport—that he wasn’t so sure about a mission after all, and didn’t get on the plane. In the other situation, my companion had done something VERY against the rules (like VERY) and got shipped away.

And in both of these cases, I was left alone in my little apartment in Grants, New Mexico, with no other missionaries closer than 45 miles away.

But…. there were the McNeills. They had five boys with the priesthood, so it was like a built-in, constant splits situation. So, for two weeks I lived with the McNeills, slept on their bunkbeds, and ate at their table. (And this is to say nothing of the fact that I was in this area for 13 months, and was at their house all the time anyway.)

ARE YOU READY TO GET BACK TO THE PLOT?

One night, which I remember with crystal-clear vividness, we were sitting in the kitchen around the big wood table. The house was adobe, and very homey—there was a wood-burning stove in the kitchen, and there was always a pot of beans on the stove.

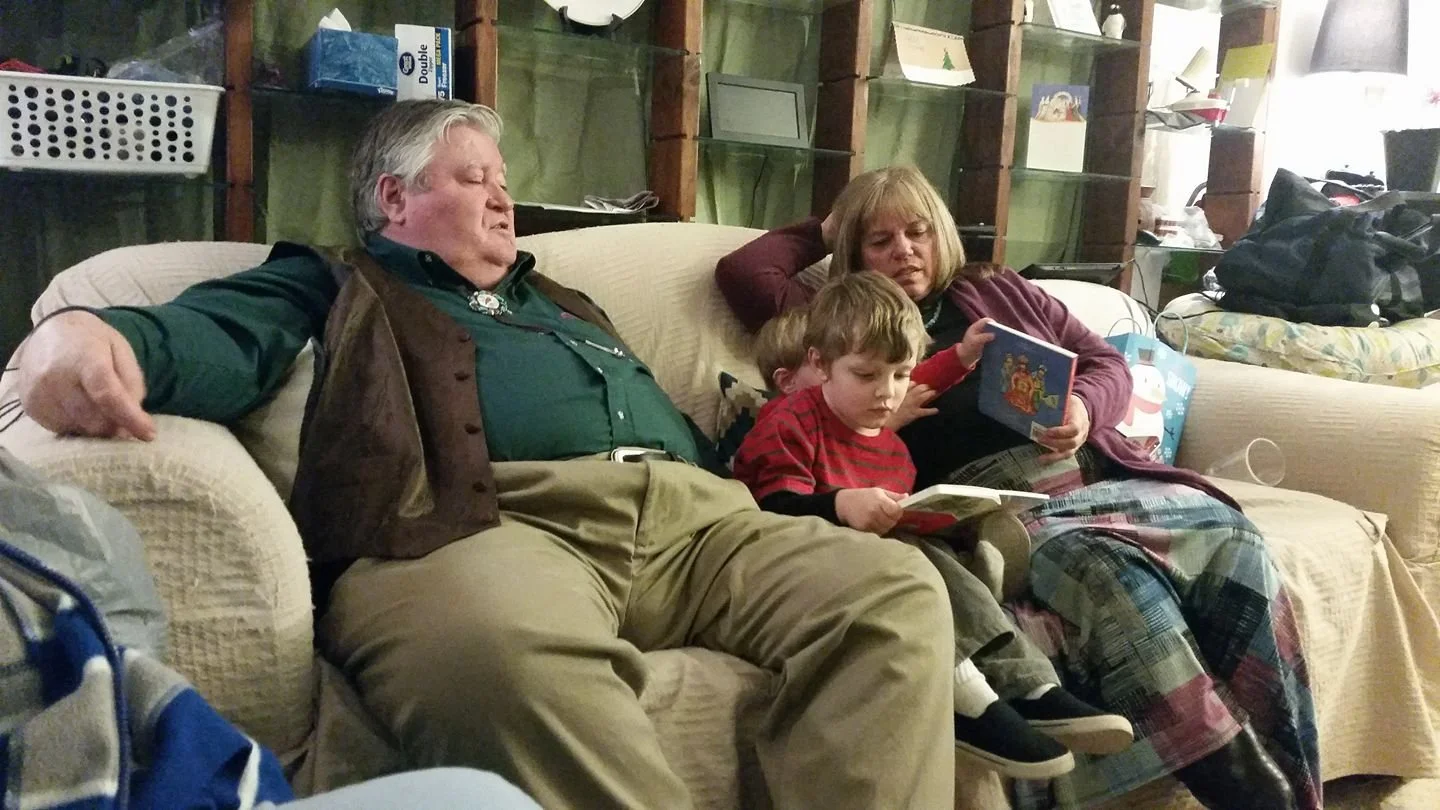

Richard and Lisa McNeill

And this night, probably due to some stupid thing that I’d said about living on the Navajo reservation, Richard McNeill began telling me the history of the Navajo people.

It is hard to pinpoint where your life changed, but that night, my life changed.

“The thing you have to realize,” Richard told me, patiently, “is that the Navajo aren’t lazy. They just have learned, over the last hundred and fifty years, that if you say ‘yes’ to white people enough, then eventually they’ll leave you alone.”

And then he began to tell me stories—stories which not only I hadn’t learned in school, but I’d learned the direct opposite.

Remember Kit Carson? The Mountain Man? Well Screw That Guy

So, in a tale as old as time, the United States government made treaties with the Navajo people, and then kept breaking those treaties. And, between 1843 and 1860, the United States continued to not fulfill their side of their obligations (like, to provide the food they had promised in the treaties, and also flaying the skin off a Navajo messenger—little stuff), so Manuelito and Barnoncito, the two main Navajo leaders at the time, decided to take the battle to the US Army.

Manuelito

And the Navajos were good warriors. They were incredible horsemen. They used guerrilla tactics effectively and often.

And so the US Army told Kit Carson, the fabled mountain man who now worked for the government, to use his mountain skills and, well, completely annihilate the Navajo. What he did, in 1962, was nothing short of genocide. He began a scorched earth campaign, burning fields and killing flocks—starting in the east and moving west—until they starved or froze to death. If they were caught, the lucky ones would be sent as prisoners to Fort Crosby, and the unlucky ones would be shot.

The Long Walk

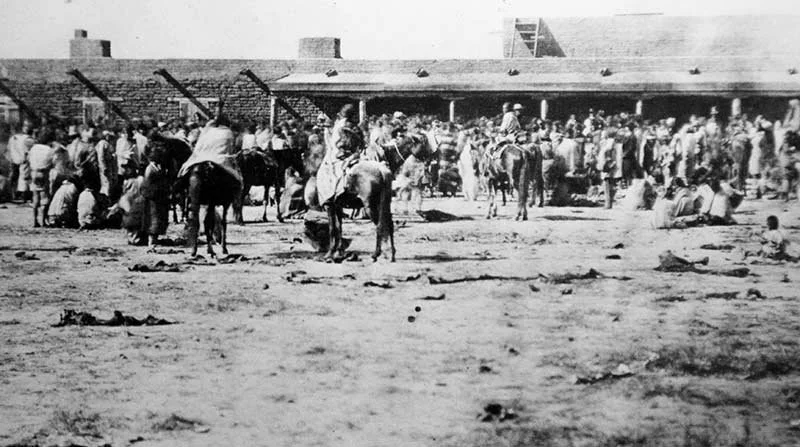

Navajos on The Long Walk

When they had backed up the Navajos as far as they could go—many fleeing into the ancestral homeland of Canyon de Chelly where they holed up in cliff alcoves until they starved to death—the US Army, in 1864, began marching the entire tribe—numbering in the tens of thousands—from Arizona to a tiny reservation south of Albuquerque called Bosque Redondo.

This was a death march. Hundreds died during the march. One particularly notable story was recorded:

It was said that those ancestors were on the Long Walk with their daughter, who was pregnant and about to give birth [...] the daughter got tired and weak and couldn't keep up with the others or go further because of her condition. So my ancestors asked the Army to hold up for a while and to let the woman give birth, but the soldiers wouldn't do it. They forced my people to move on, saying that they were getting behind the others. The soldier told the parents that they had to leave their daughters behind. "Your daughter is not going to survive, anyway; sooner or later she is going to die," they said in their own language. "Go ahead," the daughter said to her parents, "things might come out all right with me," But the poor thing was mistaken, my grandparents used to say. Not long after they had moved on, they heard a gunshot from where they had been a short time ago.

In Bosque Redondo, over the next four years, 3500 would die. They didn’t have enough water or enough fire would. And, darn it if those rascally white people didn’t give them infected blankets again. Naturally.

Bosque Redondo

Well, the point of all this was to break the Navajo, to get them to a point where they would never want to fight back ever again. To teach them the true brutality of the US Army.

And then the US made another treaty with them in 1968, and they were sent home, told to never bother fighting again.

One anthropologist said:

"collective trauma of the Long Walk ... is critical to contemporary Navajos' sense of identity as a people"

Now, to be clear: the Navajo are a regal and noble culture. They are not defeated. Kit Carson did NOT destroy them. They just learned how to deal with white people like us young dumb missionaries. They are still the proud warriors. Even if I didn’t see it.

Beyond The Long Walk

That’s only a portion of what Richard taught me about the Navajo people, but he had stories about all the tribes in the area—when I’d go out to visit a family in the tiny community of Seboyeta, he’d tell me about the battle that happened there between the US Army, the Navajos, and the Laguna. And on and on. He always had a story, always had historical insight.

It was Richard who led me to get into anthropology in college, to learn more about these cultures that I had been living among. I’ve written here before about my lifelong obsession with Chaco Canyon and the Chacoan Phenomenon—that’s all due to him. It is not exaggeration to say that if it were not for those late night chats with him, I would not be a writer. They were simply that transformative.

So why am I telling you this?

Because Richard, my friend, the man who changed my life, passed away this week. He was old. He’d lived a good life. He had a happy marriage and loving children.

I’ll just leave it with Alfred, Lord Tennyson:

Sunset and evening star,

And one clear call for me!

And may there be no moaning of the bar,

When I put out to sea,

But such a tide as moving seems asleep,

Too full for sound and foam,

When that which drew from out the boundless deep

Turns again home.

Twilight and evening bell,

And after that the dark!

And may there be no sadness of farewell,

When I embark;

For tho' from out our bourne of Time and Place

The flood may bear me far,

I hope to see my Pilot face to face

When I have crost the bar.